In 1985, Steve Meretzky at the game studio Infocom imagined the futuristic metropolis of Rockvil, South Dakota, at the centre of “The Quad-State Region” – a sprawling urbanization throughout North and South Dakota, Montana, and Wyoming, all connected by “skycars”. Though “A Mind Forever Voyaging” may remain in the realm of fiction, by the real year 2031, it may indeed be possible to fly from Bismarck to Belle Fourche in a personal eVTOL aircraft.

The dream of the flying car has also been a powerful inspiration for Robbie Lunnie, an associate professor at the University of North Dakota School of Aerospace Sciences, who briefed the 2024 Fly-ND conference on plans for Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) and Urban Air Mobility (UAM).

Advanced Air Mobility is a coalescing set of operating principles to handle the coming wave of what could be glibly called human-sized drones. The development of high-powered lithium ion batteries, lightweight electric motors, and advanced control software that enabled the quadcopter RC revolution a decade ago has finally resulted in several viable machines, some of which may be FAA certified as early as 2025.

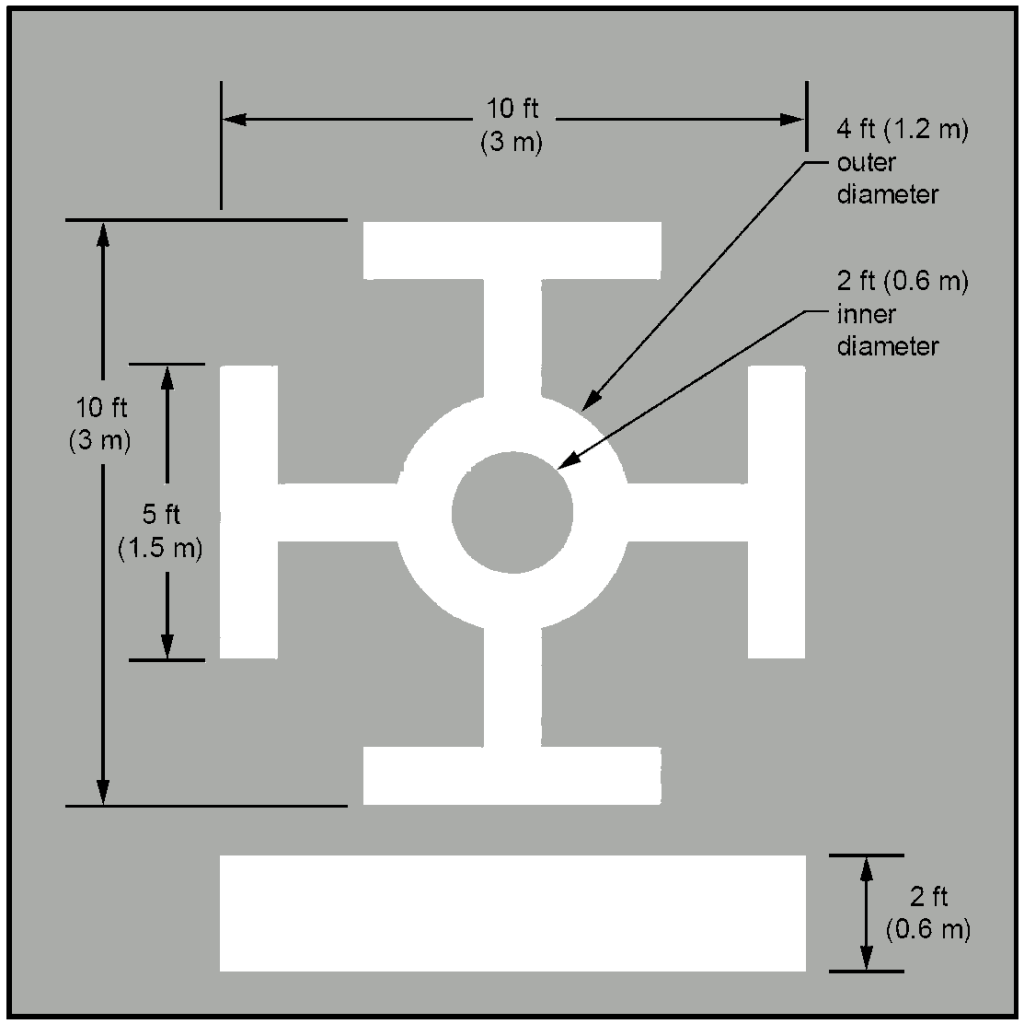

Expecting another wave of low-skilled users to the national airspace, NASA and the FAA have scrambled to get ahead of the problem, developing standards for AAM operations and facilities, and intentionally separating the coming traffic from existing heliports, which are mainly equipped only for professional pilots and gas-guzzling motors, instead focusing on developing new “vertiports” more properly equipped to recharge electric aircraft and handle passengers.

AAM will first be tested in rural locations like North Dakota – the wide open spaces, existing UAV testing environments, and the presence of one of the world’s largest aeronautical educational facilities, would seem to make the region a nearly perfect proving ground for new aviation concepts. Lunnie has already sketched out where one Vertiport may go – adjacent to the Fargo Aero Center at Hector International Airport, already a common transit point for Air Taxi clients. Another potential location? As close as possible to Lunnie’s own home in Thompson.

Urban Air Mobility applies AAM principles to the crowded space in and above cities. The dense traffic and limited available land means that uses may encounter a variety of access points, like small “Vertistops” and larger “Vertistations”, with aircraft moving along designated Urban Air Corridors. These corridors will be specially defined streets in the local airspace, which will be laid out in cityscale AFR (Automated Flight Rules) maps much like the familiar but longer-range VFR sectional charts of today. These streets in the sky will be at different altitudes based on direction of travel and whether passing is needed – and as AAM/UAM has developed, their planned altitude has risen from about FL015 in early concepts to around FL050 now. More space to work with means more safety margin in flight.

If that sounds like you’re going to need a pilot to figure it all out, you’d be right. Even though AAM/UAM expects a great deal of computerized assistance for passengers, as the first models are starting out, your eChopper will come with an onboard pilot. That could change later on, but not because of AI. Aviation has tons of existing infrastructure and uses in America, and there will always be a lot of problems to navigate around. Autonomous systems can only go so far, so the real future of “driverless” eVTOL is Turking. Much like the luxury “self driving” cars of today, a gaggle of telepresent pilots at the far end of the cellular network will be standing by to handle your takeoffs and landings. Eventually, centralized control centres could see as many as 5 flights monitored by a single certified pilot, pending the results of time and attention studies being conducted by UND and other researchers. In such a future, pilots wouldn’t be obsolete, but the offered jobs may lack the thrill of skyward motion.

Finally, how to power it all? The electrical demand from Vertiports may prove to be a unique challenge even greater than the EV revolution, if fast-charging of fixed batteries is relied on. Alternatives like drop-and-swap battery switching have also been floated, but Lunnie doesn’t think such swaps will be a feature of approved aircraft because of how the FAA regards safety matters. Presently, battery servicing is a job for certified mechanic. Landing on a spare battery could also cause a fire, so the draft EB-105 vertiport standard presently does not allow for padside storage of battery packs. Other energy sources are left entirely to future consideration.

There are still a lot of rough edges mixed with “gee-whiz” hype in the AAM/UAM mindspace. In practice, the economics may prove unfavourable in many ways, particularly when considering rural distances and load factors for AAM testing, then proceeding to the conflicting land use priorities and noise abatement measures sure to cross paths with UAM. Still, democratized flight accessible from the next street corner over is the sort of 21st Century amenity we’ve always hoped would arrive.